Our reading this week juxtaposes two very different things: the Sotah and the Nazir. A Sotah was a woman suspected of being unfaithful to her marital vows. If, instead of admitting what she had done, she agreed to a Divine test in the Holy Temple, then if she had not done wrong she would be blessed, but if she had she would die. A Nazir, on the other hand, is a person who makes a special vow to abstain from wine or becoming impure.

These two things appear at first glance to be polar opposites, with no connection. The Sotah is someone who may have done a very unholy, degraded thing. The Nazir, by contrast, is a person who makes a special vow to stay in a holy state. So why would the Torah discuss one next to the other?

The Talmud asks precisely this question (Sotah 2a), and quotes a teaching from Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi, the one who recorded and arranged the Mishnah, to answer it. “Why is the Torah portion of the Nazir next to the portion of the Sotah? To tell you that one who sees the Sotah in her defilement should withdraw himself from wine.” Alcohol can lead a person to do things he or she might otherwise avoid, and the Torah is saying a person exposed to how far that might go should feel compelled to avoid even the first step.

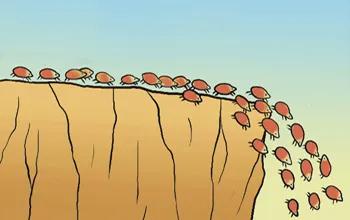

It is human nature to be drawn to the behavior and thinking of others. There is a well-known phenomenon called the “copycat effect,” in which people are inspired to duplicate a previous crime covered in the media.

What is less obvious is that the actions of others have an insidious effect even upon those of us not at risk of becoming murderers ourselves simply because we watched coverage of one on TV. The Torah is not saying that the average person who witnessed a Sotah is somehow at risk of going out and being unfaithful, but rather that people become inured to bad behavior the more they hear about it.

This concept is also found in the Cities of Refuge, described in the last reading (Masei, 35:10-15) of Bamidbar (Numbers), the current book. These cities were allocated for those who carelessly but unintentionally killed someone. Such a person was forced to go live in one of these cities for the rest of the lifetime of the High Priest, as an atonement. This is discussed in the Talmud in the second chapter of Makkos, p. 9b ff.

The layout of these cities, though, is such that they cover unequal amounts of land and population. There were six cities, tracing roughly parallel vertical lines on each side of the Jordan river. They were also equidistant, at one-fourth, one-half, and three-fourths of the way from north to south in the Land of Israel. This meant that the northern and southern cities were the nearest refuge for three-eighths of the people, while those in the center covered only one quarter. Furthermore, because only two and one-half tribes lived on the far side of the Jordan, the cities on that side served barely one-fifth of the twelve tribes, while the cities within Israel proper covered nearly four-fifths.

The Talmud explains this by saying that there was a greater population of murderers in those regions. Initially, it rejects this answer, because an intentional murderer was taken to court and would suffer capital punishment; that was not relevant to negligent manslaughter. The discussion concludes, however, that the two are related: in a place with actual murderers, others were susceptible to being more careless in situations where their behavior might endanger others.

Think about that! The Torah is teaching us that the “copycat effect” doesn’t merely impact those who might actually do the same. It affects all of us, by making the inconceivable conceivable, at every level.

Our task, then, is not merely to not be drawn to bad behavior and false ideologies, but to deliberately move ourselves in the opposite direction, to prevent these bad influences from affecting what we know to be the right and just path.